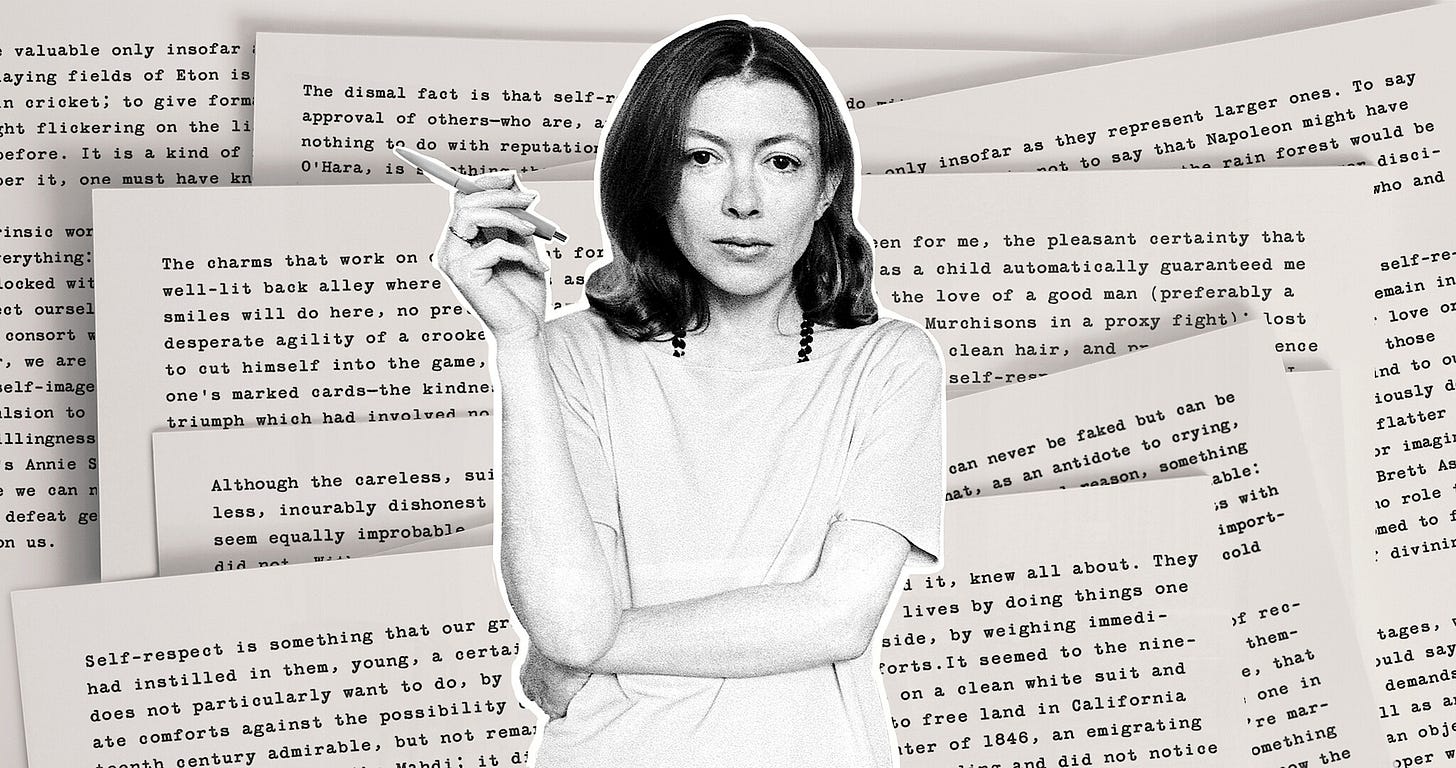

Joan Didion’s most famous quote, probably, is “we tell ourselves stories in order to live,” from “The White Album.” That was the first book I read of hers, after a recommendation from my first college English teacher that I use it for my assignment. She saw a journalist, or at least I call myself one, with too many opinions for my own good, and decided Joan would be good for me. I’m impartial, however, to what follows it.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live...We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the "ideas" with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” - Joan Didion, The White Album

If you’re like me, you didn’t know what phantasmagoria meant, so phantasmagoria is a sequence of real or imaginary images like those seen in a dream (and apparently, a 90s video game).

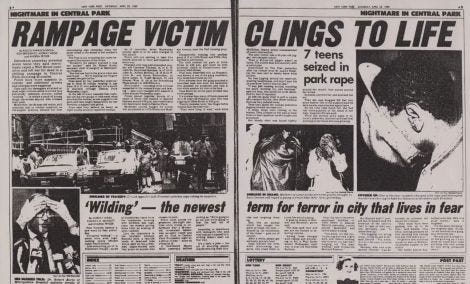

She mentions the murder of the five, referencing her 1991 essay “Sentimental Journeys” written for The New York Review — a piece of social and political commentary on the trial of the Central Park Five. A 29-year-old investment banker went for a jog in Central Park around 102nd for seven or eight miles. She was found at 1:30 later that evening missing 75% of her blood and her clothes, her skull crushed and twigs in her vagina. It’s a crime that left New Yorkers shaken — not an easy feat. Didion wrote about the five Hispanic and Black teenagers that were prime suspects in the rape.

Matias Reyes, a serial rapist, later confessed to the assault in 1989. The five men were released from prison and sued the City of New York for malicious prosecution, racial discrimination, and emotional distress. The suit was settled for $41 million.

What was initially a case about New York’s lawlessness of youth and female violence became an example of inequality and a pertinent showing of racial profiling and discrimination. Here is where Didion’s discourse comes in. She releases “Sentimental Journeys,” nearly 16,000 words long, about the discourse surrounding racism within law enforcement. Peter Noel, a race writer for The Village Voice, reflected on this essay during a remembrance event I attended earlier in the month. He said the black community was in shock that they agreed with this white woman, that she was right, and that she was saying it on such a large scale. She believed “the case could be read as a confirmation not only of their victimization but of the white conspiracy they saw at the heart of that victimization.”

Joan was a standout figure in the new wave of journalism, dominated by men. She cast a coolly distant eye over American dystopia, offering cultural and literary criticism on everything from The Doors to the Manson murders. She wrote for the Times, Time Magazine, New York Review, and countless other publications. Her husband and child died within a year of each other. Instead of wallowing in grief, she produced a Pulitzer Prize finalist memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking.”

“I know why we try to keep the dead alive: we try to keep them alive in order to keep them with us,” Didion wrote in the memoir. “I also know that if we are to live ourselves there comes a point at which we must relinquish the dead, let them go, keep them dead.”

I read this book in a single sitting, lazing on an inflatable pool float in the static heat of June. I’d always had an odd relationship with death. My parents say I talked to ghosts as a child, and I have a history of predicting deaths in the family. It’s a premonition type of thing, like when I have the urge to call my father about my mom’s Christmas present in October before a midterm. He answered the phone with “how did you know?”

“The Year of Magical Thinking” reflects on grief from the inside, yet there’s a detached aspect (as there was in most of Didion’s writing). She turned her immense pain into art, and yet it wasn’t for monetary value — while we as humans understand that a woman in the public eye who loses two of her closest family members would be hunted. Society would analyze the scraps of emotion and appearances she gave, grasping at straws to tie in the death of her more famous friends. People revel in the pain and suffering of others. You just can’t quite look away. Didion coped with the losses in the only way she knew how, which was literature.

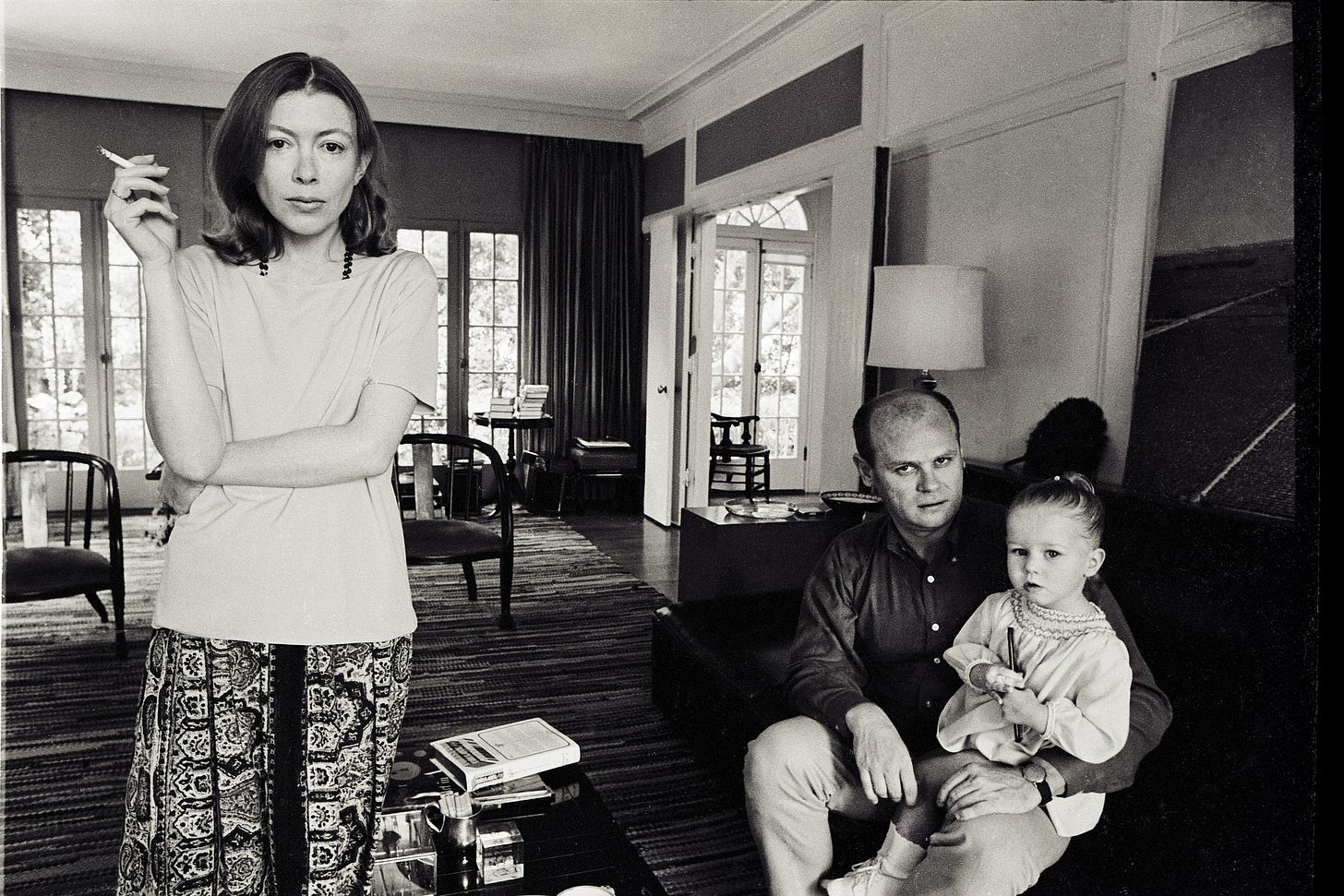

This photograph, taken by Julian Wasser, is often cut singularly to feature Joan. I even used it above, because it’s just so her. The lackadaisical stance, the cigarette, the bob, the stare. Even looking at the photo now she almost seems pasted in. Next to her is her husband, John Gregory Dunne, and her daughter Quintana Roo Dunne. I only recently began to read about her husband, and it’s only because the director of her Netflix documentary is her nephew of the same surname, and it reminded me of Amy Dunne (via Gone Girl).

Did she know? When she got married? What the Dunne name would be synonymous with? Perhaps it’s only me and other readers who associate Dunne with Gone Girl, most others probably think of Livvy Dunne.

Joan Didion and Gone Girl to me are quite similar for some reason. I can’t explain why. Maybe it’s the pessimistic outlook, maybe it’s the misplaced marriage or the New York writer pairing. I think Joan could be Amy, but Amy couldn’t be Joan.

Another thing: “In Bed.” Written around 1990. It’s included in “The White Album.” It’s about her migraines, and although I’ve only read it once, something about it stuck with me. I have vicious migraines that can leave me puking over the toilet or burrowed in the dark with a bag of peas over my eyes. (Btw, the ‘Hungover AF’ hat that Alix Earle has, I’ve had for years because of my migraines. This is migraine erasure and now people assume I’m hungover! Disrespect.) I get hot flashes, sometimes there’s a bright white spot in my vision. And it’s at my lowest when I remember a quote from Didion.

“That no one dies of migraine seems, to someone deep into an attack, an ambiguous blessing.”

In 2003, she was being interviewed by The Guardian, and she recalled when she was 10 years old, writing a story about a woman who killed herself by walking into the ocean. She wanted to know what it would feel like (in order to have the most accurate description, in true Didion fashion). I understand. The ocean looks so entrancing when you stand on the shore. The waves are hypnotizing, the tide pulls you in…

Joan said she nearly drowned on the beach that day and never told her parents. She told the interviewer, “I think the adults were playing cards.”

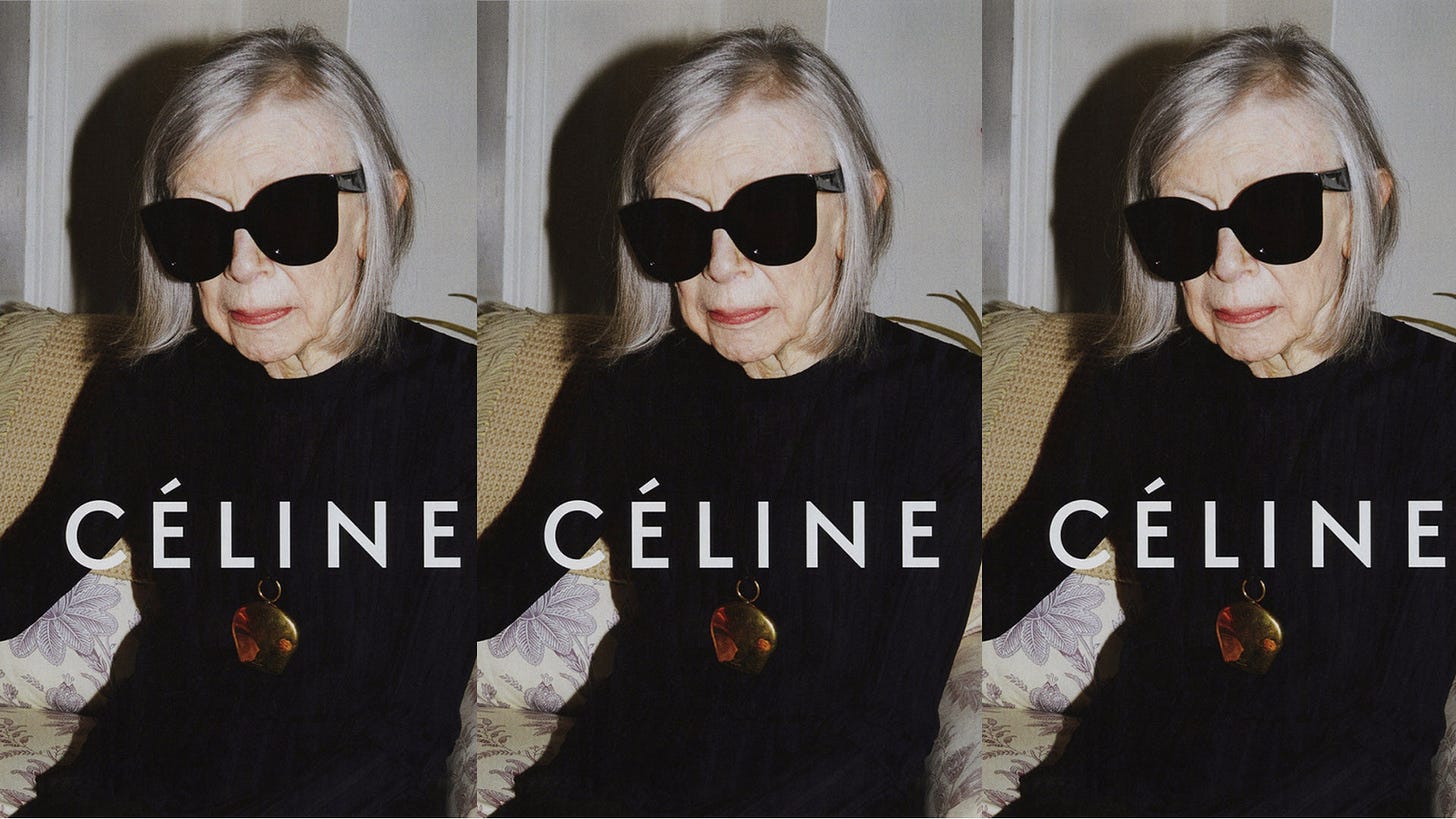

She was friends with Sylvia Plath. Janis Joplin crashed her house party. Christopher Isherwood referred to her as “Mrs Misery”. Natalie Wood shared her closet. And yet, I believe the most beautiful parts of her life were the things she kept so close to her chest. She was incredibly protective of her writing and lost her only ‘editor’ when her husband died. At the age of 80, she was the face of Céline, ever graceful, and always in sunglasses.

I could talk about Joan for hours upon hours, and dissect every single one of her essays piece by piece. You could reframe her sentences one by one until you realize that her prose is inevitable.